Project Proposal: What Explains California?

In these studies I have sought to re-name the things seen, now lost in a chaos of borrowed titles, many of them inappropriate, under which the true character lies hid. In letters, in journals, in reports of happenings I have recognized new contours suggested by old words so that new names were constituted. . . . it has been my wish to draw from every source one thing, the strange phosphorous of the life, nameless under an old misappellation.

—William Carlos Williams, In the American Grain

Due Date: Thursday March 10th “What Explains California? Project Proposal

Proposal Description We will complete our reading of Phillip Fradkin’s The Seven States of California by Spring Break. The second half of our course will be organized around individual writing projects.

The first step in the process is you working to design the project around primary source material. You have over a week to explore the materials I have put on the course web site. You need to explore the materials to find what most interests you, and to begin articulating for yourself what that interest really is. The examples we will go over in class are primarily digital archives that include both primary and secondary materials available on the web

Organization of Proposal The four-part proposal will include the following elements:

- A one-sentence summary of the project: name the materials and/or artifacts you are working with and the archives you are accessing. (Include the URL for each of the archives.)

- A one-page, single-spaced description and elaboration of your project: What interests you about the material you have chosen? What do you hope to find out? What are the key terms that are associated with the artifacts or materials?

- A list of primary sources: Drawings and sketches, Photographs, Correspondence, films, first-person narratives, journals, government documents, ledgers, etc.

- A list of secondary sources: articles, books, curated document or digital collection introductions

Primary Materials for What Explains California? Projects

“American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.

—James A. Baldwin

“California is America—only more so”

—Carey McWilliams)

Where do I begin? A Case Study of Oakland Museum Collections

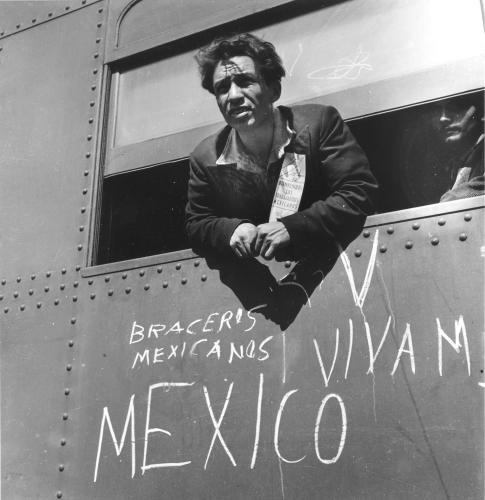

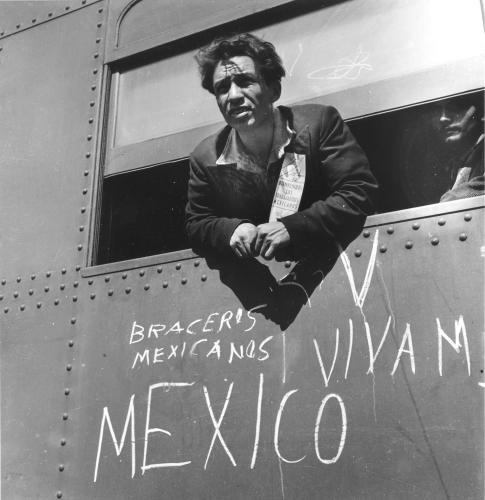

Mexican worker arriving in the U.S. during early days of the Bracero program in 1942. First Braceros. ca. 1942. Dorothea Lange. Collection of Oakland Museum of California

Picture This: California’s Perspectives on American History is an educational resource that features primary source images from the Oakland Museum of California’s collections that reflect the rich cultural diversity of California.

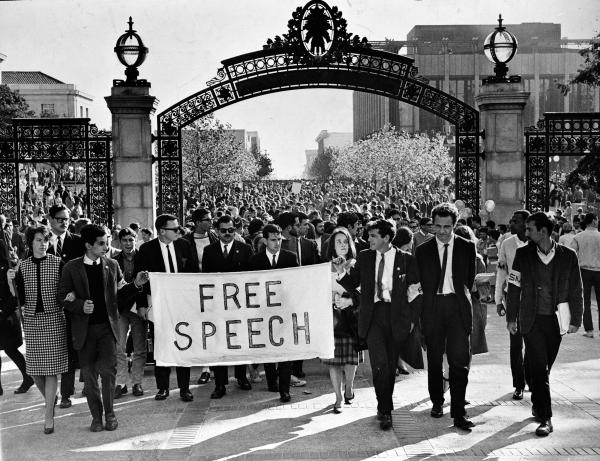

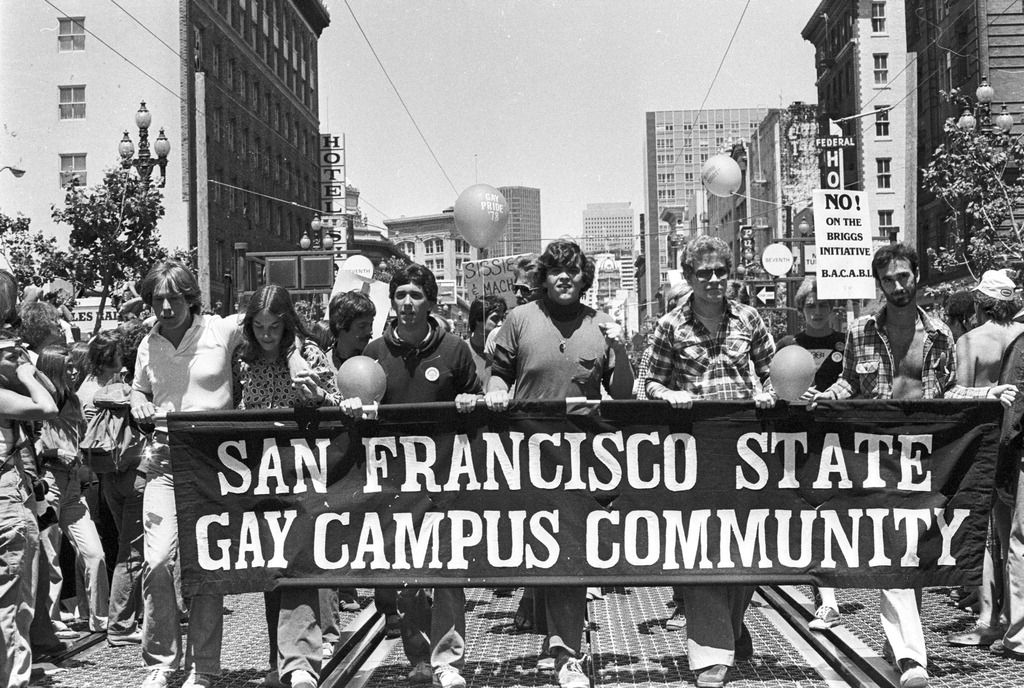

Iconic Images of the 60’s in California The 1960s were an extraordinary time in California. These are a few images of some of the amazing things that were happening.

Immigration Exhibit I am interested in showing how contemporary America at the turn of the century and throughout have documented immigration through the use of photography. This exhibit allows to showcase a unique lens from the photographer.

More Featured Exhibits

A Highlight of Materials Accessed through Digital Portals Below I highlight some materials and collections from two digital portals: Selected Digital Collections and Materials at the Library of Congress and selected collections and materials at Calisphere: a gateway to digital collections in California’s public libraries, archives, and museums.

Film

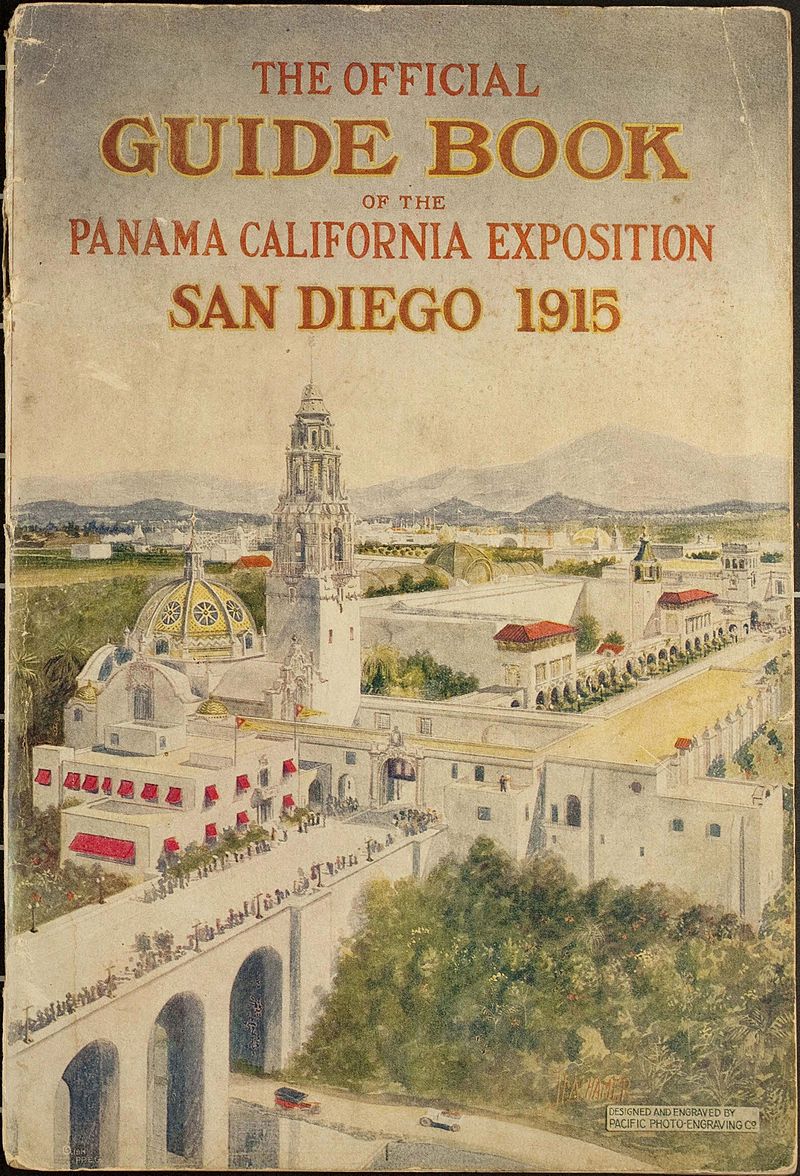

Before and After the Great Earthquake and Fire: Early Films of San Francisco, 1897 to 1916 This collection consists of twenty-six films of San Francisco from before and after the Great Earthquake and Fire, 1897-1916. Seventeen of the films depict San Francisco and its environs before the 1906 disaster. Seven films describe the great earthquake and fire. The two later films include a 1915 travelogue that shows scenes of the rebuilt city and a tour of the Panama Pacific Exposition and a 1916 propaganda film.

Photography

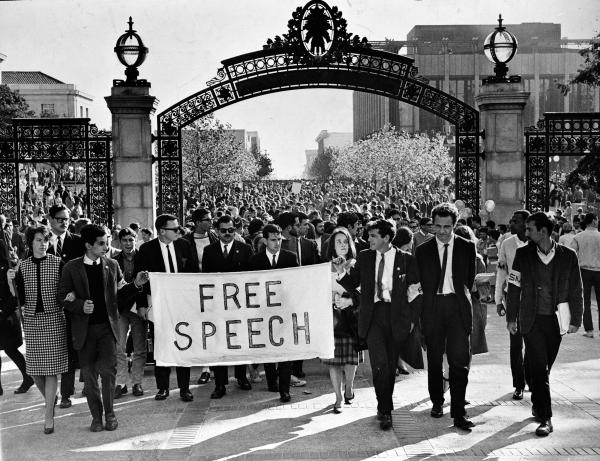

Free Speech Movement leader Mario Savio leading student protestors at the University of California, Berkeley. Nov. 20, 1964. Chris Kjobech,. Oakland Museum of California. The Oakland Tribune Collection.

Lawrence and Houseworth Collection In 1867 the Library of Congress acquired a set of more than 900 albumen silver half stereographs published by Lawrence and Houseworth of San Francisco. The acquisition also included the third edition of Gems of California Scenery, a catalog listing titles for all the views published by the firm. This was one of the Library’s earliest photographic acquisitions. The images date from 1862 to 1867. The photographs depict major settlements, boom towns, placer and hydraulic mining operations, shipping and transportation routes, and such points of scenic interest throughout northern California and western Nevada as the Yosemite Valley and the Calaveras Redwoods. The collection also includes an extensive pictorial survey of mid-nineteenth-century San Francisco.

Ansel Adams’s Photographs of Japanese American Internment at Manzanar Digital scans of both Adams’s original negatives and his photographic prints appear side by side allowing viewers to see Adams’s darkroom technique, in particular, how he cropped his prints. Adams’s Manzanar work is a departure from his signature style landscape photography. Although a majority of the more than 200 photographs are portraits, the images also include views of daily life, agricultural scenes, and sports and leisure activities (see Collection Highlights). The web site also includes digital images of the first edition of Born Free and Equal, Adams’s publication based on his work at Manzanar.

Narrative

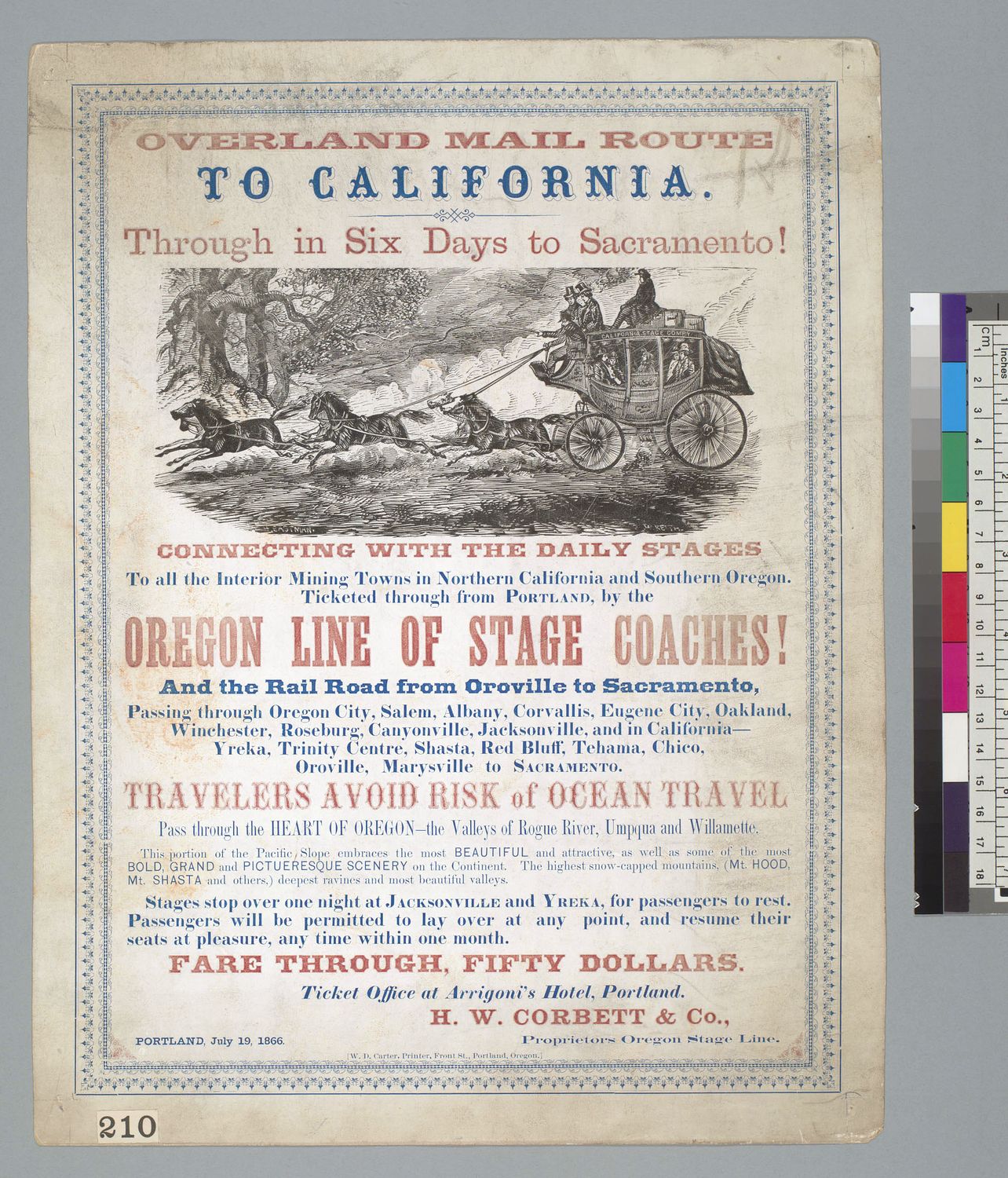

California as I Saw It: First-Person Narratives of California’s Early Years, 1840-1900 The books in this collection are first-person accounts from the time of the Gold Rush and California statehood through the turn of the century. They provide detailed information about localities and people important to the state during the latter half of the nineteenth century, when large numbers of English-speakers flowed into the far West, encountering a variety of Native American groups and the Spanish-speakers who had preceded them to the region. The accounts convey a sense of America’s westward movement in the post-pioneer era and offer the emigrants’ reactions to the wilderness environment they traversed and settled.

History

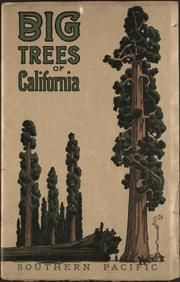

The Evolution of the Conservation Movement: 1850-1920 documents the historical formation and cultural foundations of the movement to conserve and protect America’s natural heritage, through books, pamphlets, government documents, manuscripts, prints, photographs, and motion picture footage drawn from the collections of the Library of Congress. The collection consists of 62 books and pamphlets, 140 Federal statutes and Congressional resolutions, 34 additional legislative documents, excerpts from the Congressional Globe and the Congressional Record, 360 Presidential proclamations, 170 prints and photographs, 2 historic manuscripts, and 2 motion pictures.

Music

The WPA California Folk Music Project The WPA California Folk Music Project [1938-40] was the result of a joint effort of the Work Projects Administration, the Library of Congress, and the Music Division of the University of California, Berkeley. It was officially sponsored by the University of California at Berkeley and co-sponsored by the Archive of American Folk-Song, then in the Music Division, at the Library of Congress.

The Ethnographic Experience: Sidney Robertson Cowell in Northern California From 1938 to 1940, while in her thirties, Sidney Robertson, ethnographer and collector of traditional American music, single-handedly organized and directed a California Work Projects Administration project designed to survey musical traditions in Northern California. The result of the project was a remarkable, and quite modern, multi-format ethnographic field collection–the WPA California Folk Music Project. Not only did the project generate a wealth of musical and cultural documentation from a wide variety of groups at a certain point in California history, it also provided, through the ebullient presence of Sidney Robertson, a vicarious experience of what it means to do ethnographic fieldwork. The value of this multi-faceted collection is that one is invited to hear the voices, see the faces, and sample the cultural context of the performers being recorded.

Humboldt State University

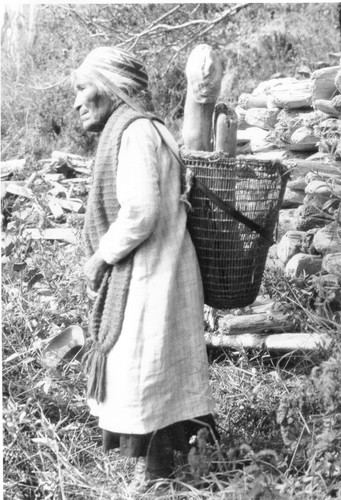

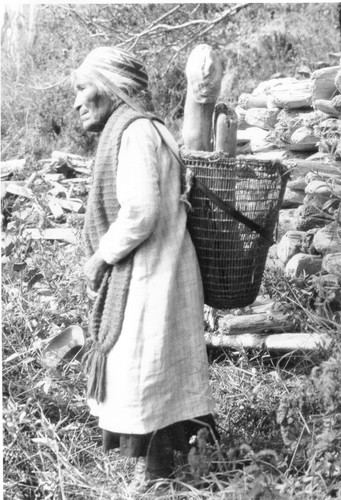

Mary Ann Frank, carrying driftwood in a burden basket. Roberts Photography Collection. Humboldt State University Library

The Roberts Photograph Collection documents life on the Yurok Indian Reservation along the lower Klamath River in northwestern California during the period of 1915-1933. The private collection of Mrs. Ruth Kellet Roberts contains 536 photographs, many of them taken by Mrs. Roberts. They include photographs of her many friends in the Yurok Indian community and their daily activities and ceremonies, early photographs of the town of Requa, of the Pecwan-Johnsons area, and various landscape features of the surrounding area

The Ericson Collection depicts a wide variety of everyday northwest California scenes and activities from the 1880s through the 1920s. Lumber industry, Native Americans, city and village street scenes (primarily Arcata ), Schools, portraits, and scenic views are the featured subjects of this collection. The primary photographer represented is A.W. Ericson with some by his son and business partner, Edgar.

Riverside Public Library Fruit Label Collection The Citrus Label Collection consists of citrus labels (mostly orange, but some lemon and grapefruit examples) mainly from the southern California counties of Riverside, San Bernardino, Los Angeles, and Orange. The collection ranges from early naturalistic labels like Gypsy Queen (1891) to a later example of commercial art, Terra Bella (1952). The subjects featured on labels in the collection vary widely and include sports ( Athlete); animal and floral designs ( Mallard and Camellia); architectural and natural landscapes (Mission Bridge and Yosemite); portraits of women and children (Co-Ed and Vulture ); marine scenes (Chinook); western and other historical images.

Invisible-5

Invisible-5  Bible of Black Travel

Bible of Black Travel